Posted on May 25, 2020

SHOOTING THROUGH AUTOMOTIVE GLASS PT. 2

SHOOTING THROUGH AUTOMOTIVE GLASS PT. 2

In Part One of this article I addressed the virtues of remaining inside of the vehicle during an adversarial encounter even if the vehicle is immobile (trapped in stopped traffic, pinned in place in such a manner that I can’t drive off, or wrecked out, etc.) by ensuring that the doors are locked, windows up, transmission in park (or neutral if a manual transmission), and the parking brake engaged. I also discussed the importance of unlatching the seat belt buckle in order to not get tangled up in or pinned in place. This should be followed by immediately calling 911 and keeping the other motorist in sight as much as possible, all the while watching for visual clues that would suggest that an attack might be imminent. However, everything changes if my vehicle is immobilized and I am approached by another with a handgun or a long gun like a rifle or shotgun.

I have completed vehicle combat and tactics classes in which we shot up the passenger portion of an automobile in order to gauge the effectiveness of bullets fired from handguns and centerfire rifles as well as shotgun slugs. While bullet performance might be compromised by the body of a car, they were effective at getting inside the cab with plenty of energy much of the time. As far as windows and windshields go, I will simply say that I want to be somewhere else other than inside the cab of that vehicle at that time. Another reason that I do not want to remain in my vehicle during a gunfight is that I can easily be flanked even by a single adversary. Due to the fact that I am unable to turn my body much past 90 degrees left or right, I am extremely vulnerable to incoming fire from the rear directed at the back windshield and the left and right rear passenger windows. I need to get out of that car as soon as possible. In my opinion, the best way to achieve this as safely as possible is to exit my vehicle as soon as I see a firearm in the hands of an adversary before he or she is close enough to use it effectively.

Unfortunately, this may not be case in many road rage incidents. Attempting to exit the vehicle while in close proximity to an armed individual who decides to start shooting is not a good idea. He or she is in a position for several seconds to shoot at me during which time I am unable to fight back. If that is the case, then there is indeed one thing that I can do, and that is engage my attacker through the glass in my vehicle with the express intention of either causing him or her to stop their attack altogether or drive him or her off long enough to provide me with a window of opportunity that will allow me to exit my vehicle more safely.

Proper technique includes squaring the hips to the target (shifting one’s body in the seat), pushing the handgun straight out so that the muzzle does not sweep my own legs, and extending the muzzle so that it is nearly touching the driver’s side window and the windshield. This is typically not the case when shooting out the passenger side window due to the distance of the same side window from me. It is possible to engage a threat from the passenger side window with a passenger in the seat, but this is a technique that should be learned under the watchful eye of a qualified instructor, and I am intentionally refraining from providing specifics on that technique in this article.

Concealed carriers should be aware of the following when contemplating shooting through automobile glass:

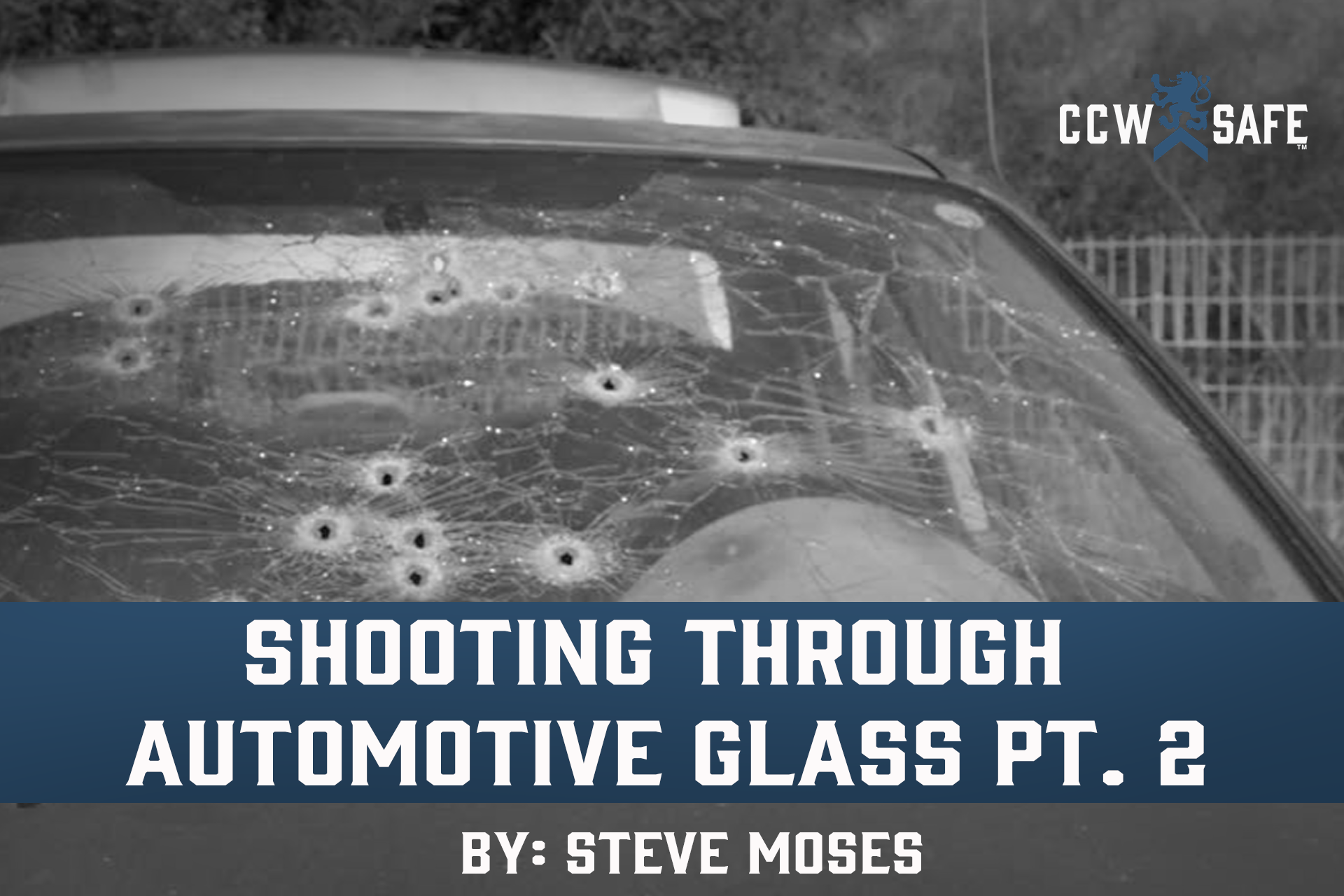

- Glass can be hard on bullets, especially glass found in the windshield of vehicles. A bullet passing through glass may become damaged, which can negatively affect its performance and alter the trajectory of the bullet enough to cause a miss if the distance is great enough.

- Tempered glass in the side windows will usually break into small pieces and fall out of the window frame. One exception to this is when side windows have been tinted (window tint is typically a plastic film applied to the glass in order to reduce the amount of sunlight penetrating the glass).

- The windshield of a car or truck is made of laminated glass. Windshields consist of two separate sheets of glass that are separated by a thin sheet of plastic and then laminated during the manufacturing process by being subjected to pressure and heat. This is why automobile windshields typically do not break into separate shards of glass during a vehicle accident and lacerate the occupants. It is extremely tough, and when shot tends to remain remarkably intact. A handgun or rifle round typically drills a hole through the windshield accompanied by a portion of the windshield cracking.

- In addition to being laminated glass, front windshields are angled (sometimes sharply) from top to bottom and the sides often curved in order reduce wind resistance. The reason that this matters to concealed carriers is that both the toughness of the glass and angular surfaces means that the chances are good that that the path of the bullet will be deflected as a result of passing through the glass. The amount of deflection can vary from slight to wildly off-course. Handgun bullets typically deflect upwards when being shot through a vehicle windshield and can also be deflected to the left when shot from the driver’s side and deflected to the right when shot from the passenger’s side. For example, I attempted to shoot an eight-inch circular target approximately seven yards through the windshield of a junked Honda Civic sedan. I projected the muzzle of my Glock 26 so that it was in near contact distance to the windshield in order to minimize deflection to the extent possible and fired one round of Hornaday 9mm Critical Duty ammunition at the target. The bullet struck nearly eight inches above my aiming point. I witnessed nine other students in the class do the same thing using a variety of 9mm and .40 caliber ammunition and never observed a single round hit where it was aimed. The lesson here is obvious. Shooting though car windows, especially windshields, is risky as it becomes difficult to control the trajectory of the exiting round and should be reserved for close-distance emergency purposes. It is our responsibility to ensure that any bullet that leave our handgun does not hit other people, cars, animals, or structures. Unfortunately, the best way to achieve that is to obtain a solid hit on our attacker.

The objective of this article is to merely shed light on a specific tactic applicable to armed conflict in which a concealed carrier (and perhaps other occupants) find themselves in an immobile vehicle and are being approached by others who are using firearms or threatening to use firearms. This article is no substitute for training under a qualified defensive firearms trainer as it does not cover the proper way to draw and handle a handgun in a vehicle, the challenges of engaging an attacker from the passenger’s side of the car while a passenger is currently seated there, how to exit on the passenger side of the vehicle if need be, how to manage other occupants in the concealed carrier’s vehicle, and the best places to take up a position behind or around car after exiting in order to obtain maximum use of cover capable of stopping incoming handgun and rifle rounds.

My primary personal plan is to avoid getting involved in a Road Rage incident that may occur in part through mishandling on my end. If that plan fails and I am accosted by an angry motorist and/or other occupants from his or her vehicle and am unable to drive away, I am most likely going to be better off if I remain in the locked vehicle and refuse to engage while remaining prepared and ready to go to my handgun if the circumstances call for it.

No plan is perfect, and more often than not it requires tweaking along the way. As Mike Tyson allegedly said, “everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” Regardless, I would much rather tweak an existing plan than attempt to develop a brand-new plan in the midst of a rapidly unfolding crisis situation.

|

Steve MosesSteve is a long-time defensive weapons instructor based out of Texas who has trained hundreds of men and women of all ages for more than two decades on how to better prepare to defend themselves and their loved ones. Steve has completed over 80 private-sector and law enforcement-only defensive weapons and tactics classes, and has trained civilian and law-enforcement officers in six states. Moses is a reserve deputy, former member of a multi-precinct Special Response Team, competitive shooter, and martial artist. Steve has written numerous articles for SWAT Magazine and other publications. Steve is a licensed Texas Level 4 Personal Security Officer and Instructor who was Shift Lead on a mega-church security detail for seven years, and has provided close protection for several former foreign Heads of State. He is currently an instructor at Relson Gracie Jiu Jitsu/Krav Maga in Tyler, Texas and Director of Training for Palisade Training Group (www.ptgtrainingllc.com). |